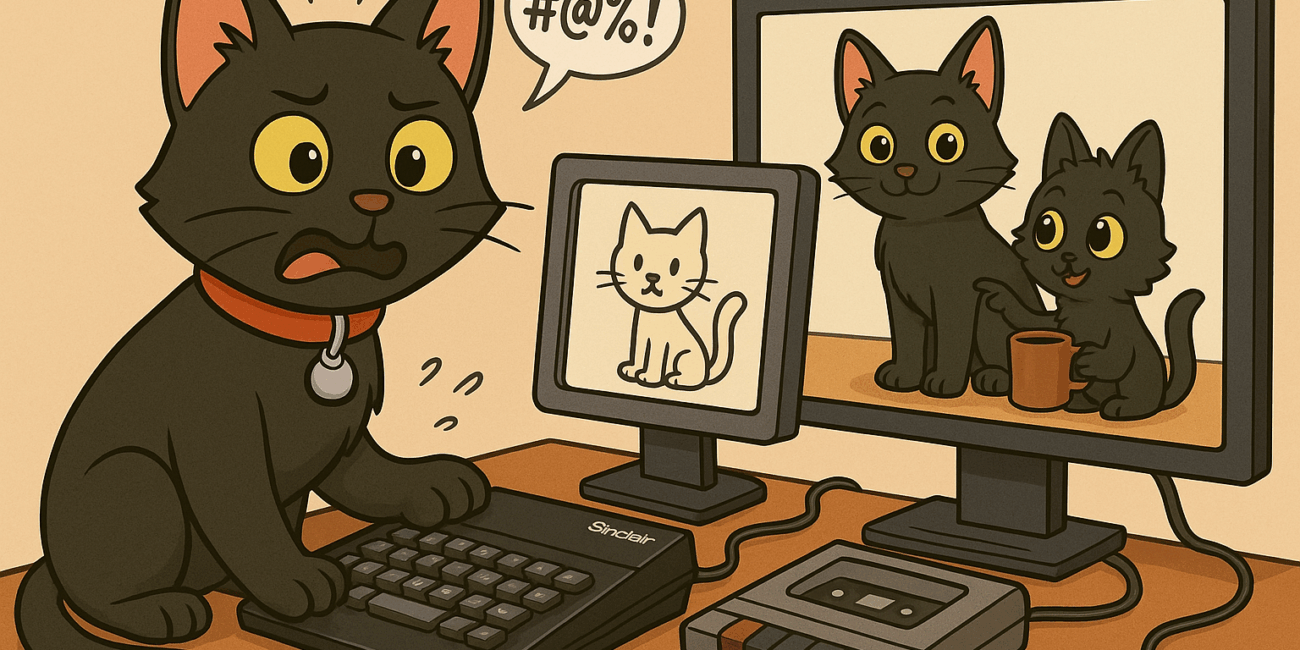

As with most of the articles on Mad Black Cat, we use an AI generated image, in context, featuring two cats who are no longer with us, to illustrate the overall content. The picture accompanying this article is showing how we use AI to generate the cartoon image of ODC and Lanson, and, apart from the occasional exception, the images are created in under 30 seconds. But how much computer power does that really take? And how would it compare to the machines many of us first typed on — like the Sinclair ZX Spectrum or ZX81?

How many ZX Spectrums does it take to draw a cat?

The answer, as it turns out, is millions. Because when you ask modern AI to generate an image — say, two cartoon cats in a living room — it takes about twenty to thirty seconds. On a ZX Spectrum from the early eighties, you’d still be waiting, and probably listening to a tape deck screeching at you.

Let’s put it into context. The Sinclair ZX81, launched in 1981, had just one kilobyte of RAM. That’s smaller than the text of this podcast script. Even expanded to 16 kilobytes, it struggled to print out a stickman. Asking it to generate a high-resolution cartoon image would take decades, if it was even possible.

Then came the ZX Spectrum. Sixteen kilobytes, or if you splashed out, 48 kilobytes. Colour graphics, enough to bring us classics like Jet Set Willy and Manic Miner, and who can forget Dizzy, the little egg. But in today’s terms, it’s tiny. Generating one AI cat picture would require millions of Spectrums chained together.

Now compare that to your smartphone — sitting in your pocket, with thousands of times the power of those early machines. And the AI I use doesn’t just run on one device. It runs on vast networks of servers, the kind of thing only governments or research labs could have imagined back then.

So next time you sigh because an AI image takes twenty seconds to appear, think of it this way: once upon a time, we waited twenty minutes for a cassette game to load, only to see the words ‘R Tape Loading Error.’ By comparison, today’s AI isn’t frustrating. It’s astonishing!

By the way, in our example we’ve spoken about creating a single image. In reality, AI tools rarely work one at a time. When you ask for an image, the system usually generates several versions in parallel — often four, sometimes more — before you even see the result. That means every thirty-second wait actually hides the effort of creating multiple complete pictures at once, discarding most and only showing you the best. It is like asking an artist to sketch four paintings in half a minute and then letting you choose your favourite.

When I was first given a ZX Spectrum as a young teen, I could not have imaged for a minute telling my future self that I would one day create this article on a mobile phone, tablet sat next to me, before starting my Chromebook to actually do the publishing… all tools the me on my ZX Spectrum could never have imagined possible, even though I was able to imagine that we would be flying around in Eagle Transporters by 1999.

“Computers may test our patience now and then, but only because they’ve spoiled us with miracles.”

Let’s Break it Down

- The ZX81 (1981): 1 KB of RAM standard (expandable to 16 KB), running at 3.25 MHz. Typing in BASIC programs was often an evening’s work, and drawing a stickman took patience. An AI image of ODC and Lanson? Forget 30 seconds — it would have taken decades of calculation, if it could even be stored.

- The ZX Spectrum (1982): 16 KB or 48 KB of RAM, with colour graphics. Fantastic for Jet Set Willy or Manic Miner, but still microscopic by modern standards. Generating one AI image would require millions of Spectrums chained together, and the poor tape deck would still be screeching.

- Modern perspective: A modern smartphone, smaller than your wallet, runs millions of times faster. The AI model that created those cats sits on infrastructure spread across data centres — the kind of thing only governments or universities could dream of in the 1980s.

- Other fun comparisons:

- That ZX81 could barely handle typing this paragraph.

- A ZX Spectrum would take years to draw a single AI-generated paw.

- One AI image = more calculations than all the moves ever played in chess history.

The ZX Spectrum in Context!

Although we have said that IF it were possible, it would take “millions” of ZX Spectrums, if we narrow it down to just 1 million Spectrums to make an image, laying them flat would cover roughly 33,120 m² — about 3.3 hectares, or 4.6 football pitches. And if you lined those Spectrums end to end along their long edge (about 23 cm each), the chain would stretch ~230 km — roughly London to Sheffield in a straight line, or London to Cardiff plus a little.

For perspective, that 230-kilometre stretch is not just a line on a map. Driving from London to Sheffield typically takes around 3 hours, depending on traffic, while the journey from London to Cardiff is closer to 2 hours 45 minutes. So, what would take you half a day on the road is the same distance your “million Spectrums” would cover in seconds of imagined AI effort.

Minor frustration suddenly feels quite modern. 20 to 30 seconds is a miracle of modern technology!

Closing Reflections

So the next time you feel a flicker of frustration when AI takes 20 seconds instead of 10, remember: once upon a time we were happy to wait 20 minutes for a cassette tape to load a game, only to see “R Tape Loading Error.” In that context, today’s “slow” AI isn’t a frustration — it’s a miracle.

And Finally…

By the way, in our example we’ve spoken about creating a single image. In reality, AI tools rarely work one at a time. When you ask for an image, the system usually generates several versions in parallel — often four, sometimes more — before you even see the result. That means every thirty-second wait actually hides the effort of creating multiple complete pictures at once, discarding most and only showing you the best. It is like asking an artist to sketch four paintings in half a minute and then letting you choose your favourite.

When I was first given a ZX Spectrum as a young teen, I could not have imaged for a minute telling my future self that I would one day create this article on a mobile phone, tablet sat next to me, before starting my Chromebook to actually do the publishing… all tools the me on my ZX Spectrum could never have imagined possible, even though I was able to imagine that we would be flying to Moonbase Alpha in Eagle Transporters by 1999.